IS THE INDEPENDENT MUNICIPAL DEMARCATION AUTHORITY BILL DESIGNED TO ALTER ELECTORAL OUTCOMES?

By Ciaran Ryan, for DearSouthAfrica.co.za

There is good reason to suspect the Independent Municipal Demarcation Authority Bill is a Trojan horse for more sinister purposes than setting municipal and ward boundaries. Whether that is true or not, the suspicions abound, as evinced by a reading of the objections to the Bill on the DearSouthAfrica.co.za public participation platform.

There are often good reasons to change a municipal boundary. For example, some residents want to be part of a municipal area with better opportunities and service delivery. But those paying rates and taxes in better-run municipalities may not want them for obvious reasons. There is a constant fear that financially distressed municipalities run into the ground by corrupt councillors and municipal managers will merge with better-resourced neighbours.

There is a crisis at the municipal level and the wards under them. The Auditor General awarded clean audits to just 16% of 257 municipalities in SA. In 2022, Ratings Afrika warned that the municipal sector was about to collapse in all but the Western Cape (where the DA has a dominant showing). This local government financial crisis has already landed at the door of the Treasury and, by extension, the taxpayer.

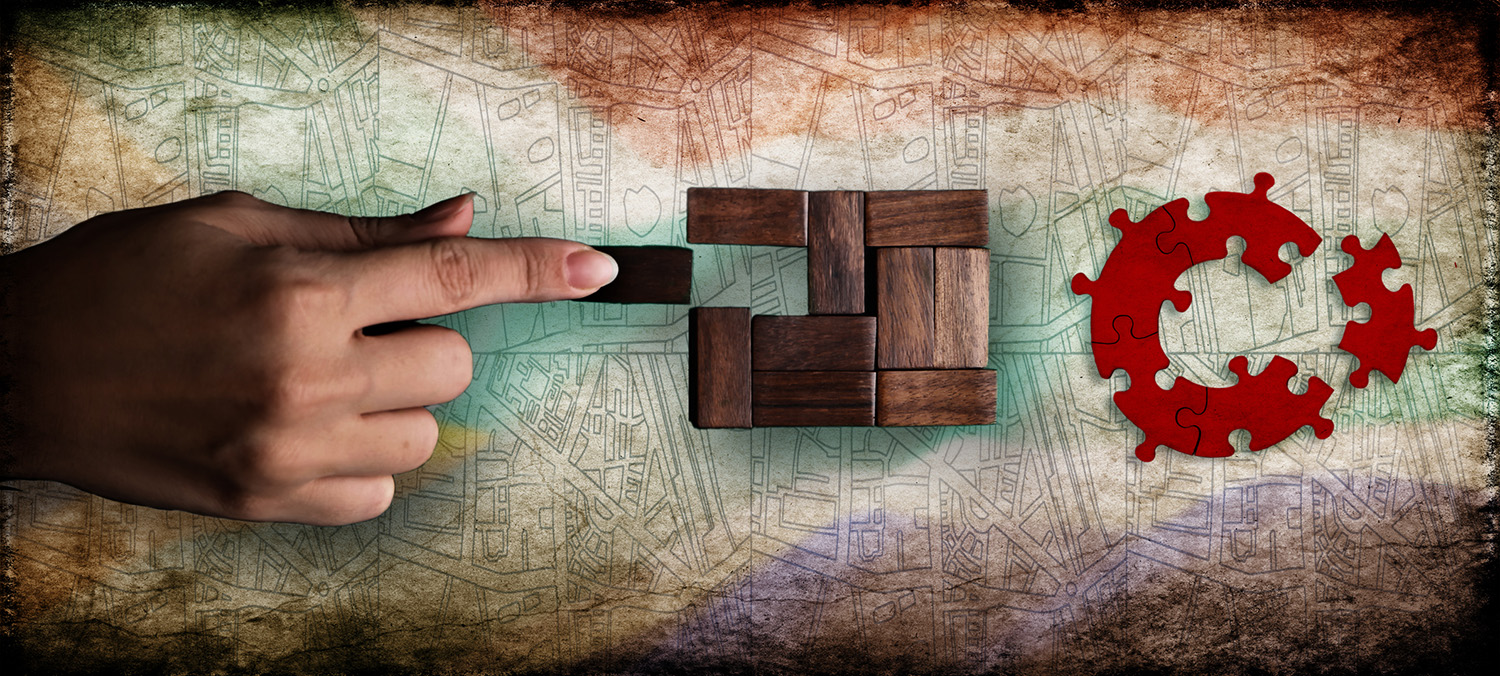

Shifting municipal boundaries has been a ruse employed by politicians for hundreds of years, even before the word gerrymandering entered the English vocabulary (gerrymandering is redrawing electoral boundaries to benefit a particular politician or party).

Consider this story from The Sowetan, explaining how Municipal Demarcation Board (MDB) chairperson Thabo Manyoni announced his intention to vacate his seat should he be elected as ANC chairperson in the Free State. His political ambitions are well known, having previously entered the race to unseat Ace Magashule as provincial ANC chair in the Free State.

The DA’s national spokesperson Cilliers Brink pointed to the conflict of Manyoni campaigning to become the ANC’s Free State chairperson while holding the MDB’s most senior post.

Those who see no problem with this are not paying attention or pretend there is nothing unusual going on here.

Then there’s this story where the ANC-run King Sabata Dalindyebo (KSD) Local Municipality in the Eastern Cape has ambitions of becoming a metro. It applied to the MDB to be granted metropolitan city status in 2026, but those ambitions have been waved aside by United Democratic Movement (UDM) leader Bantu Holomisa, just around the time the UDM led a march by disgruntled residents to the KSD municipal offices over poor service delivery. It turns out that KSD cannot run its affairs very well but now wants a seat with the big boys at the metro table.

“If they want a metropolitan city here, they must demonstrate by making sure that the budget the municipality gets from the central government is spent efficiently through the cleanliness of the city and better roads,” Holomisa is reported as saying.

You can see where this is all going: become a metro, bigger budget, happy cadres.

There is an existing structure known as the MDB, which was established in 1999 to determine municipal boundaries for the 1995-96 local elections. At that time, there were 1,262 local government bodies which were amalgamated into 843 local authorities, which were thereafter called municipalities. The Local Government Municipal Demarcation Act of 1998 gave birth to the Municipal Demarcation Board, which was established and mandated to demarcate municipal boundaries of the entire territory of the Republic. From the 284 municipalities in 2000, the country currently has a total of 257 municipalities after the municipal amalgamations carried out in 2006, 2011 and 2016.

According to section 24 of the Municipal Demarcation Act, boundary re-determinations should result in municipalities that fulfil the objectives laid out in the Constitution, most importantly, better service delivery.

A DMB research paper from June 2021 finds that “amalgamating municipalities did not result in improved service delivery.” Those amalgamated municipalities that were studied remained financially distressed. The authors proposed a moratorium on all amalgamations until more definitive results emerged, more education for councillors, and more thorough investigations prior to mergers.

Another DMB study into the reasons for demarcation requests shows four broad motivations: governance and functionality, the interdependence of people, communities and economies, spatial and development planning, and financial and administrative capacity.

Once enacted, the Independent Municipal Demarcation Authority Bill will replace the current Local Government: Municipal Demarcation Act.

The changes it introduces empower the MDB to borrow money, generate revenue, and strengthen corporate governance. It disqualifies political party office bearers and full-time employees of organs of state from being members of the board (though it is not difficult to see how this could be side-stepped – by simply resigning a political position). The new Bill requires extensive public participation prior to demarcation and obligates the MDB to publish its reasons for any changes (not currently a requirement).

The MDB may only make boundary decisions that move a whole ward in a municipality once every ten years. If it does, the MDB must do so at least three years before the next elections. This is intended to minimise the disruptive effect of significant boundary changes.

Another major change introduced in the new Bill is the Demarcation Appeals Authority, something lacking in existing legislation. The Authority will allow aggrieved parties and communities to appeal demarcation decisions without going to court and hopefully avoid some of the violent protests that have accompanied boundary shifts in the past.

This has some positives: public participation is explicitly spelt out in the Bill, and there is an appeals process. But one should always be suspicious of those looking to move boundaries around. There is a sordid history of this, and wherever it happens in the world, it is bound to provoke conflict.