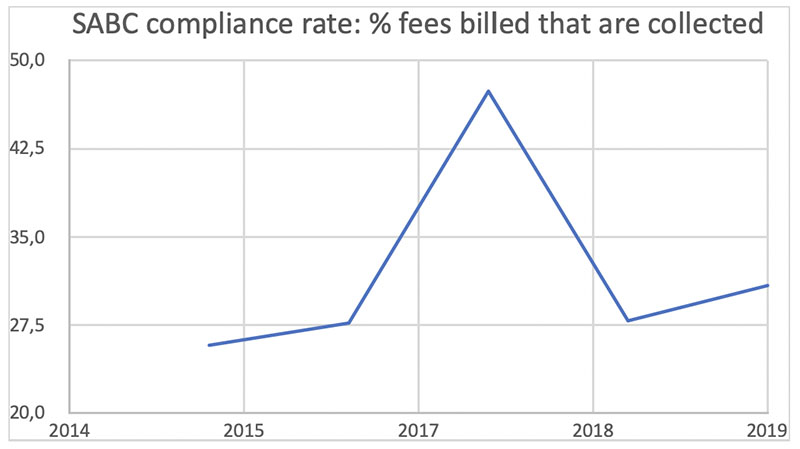

As compliance levels, already at just 30%, are tanking.

By Ciaran Ryan

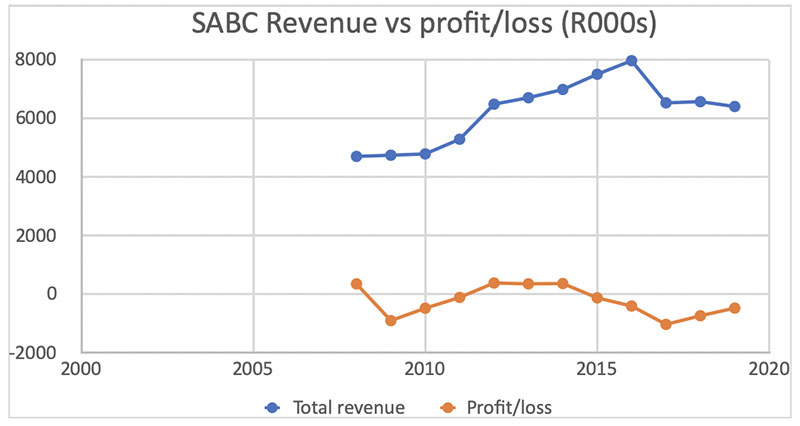

The SA Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) is in a financial pickle. Revenue has been in steady decline since 2016, and the broadcaster has made profits in just four of the last 12 years.

We recently learned from an SABC presentation to Parliament that license fee collections have been in decline during the Covid lockdown. Collection rates are already low at about 30% – or just short of R1 billion out of the R3.3 billion billed to TV viewers annually.

The SABC’s apparent solution to this is to bring in the heavies – the debt collectors (including getting Multichoice and Netflix to collect on its behalf). That will require a change to the Broadcasting Act and, of course, with that will come heavier penalties for non-payment.

Its revenue comes from advertising for the most part, sponsorships, license fees and government grants.

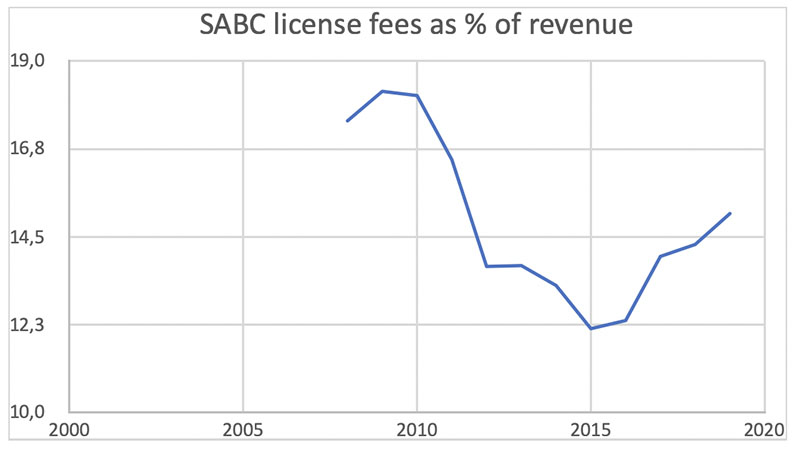

Ten years ago, license fees accounted for more than 18% of total revenue. Today it is about 15%, having been as low as 12% in 2016 during the dark days of Hlaudi Motsoeneng’s bizarre rampage through the corporation (he lied about his qualifications, awarded himself a fat salary increase and insisted on covering cuddly stories about ANC ministers attending luncheons).

The SABC finally sacked Motsoeneng as chief operating officer in 2017, but the damage was done. The graph below paints a picture of a state-owned broadcaster in the throes of state capture.

During the Covid lockdown, levels of compliance in license fee payments has deteriorated below the already weak 31% reported in 2019. The Department of Communications and Digital Technologies, under which the SABC falls, wants to overhaul the Broadcasting Act to beef up the broadcaster’s powers to collect TV licenses and impose tougher penalties for non-payment.

Among the ways it plans to do this is by handing over accounts that are 60 days overdue to debt collection agencies to collect the R265 annual license fee. This has drawn robust comment from South Africans fatigued by stories of yet another distressed state-owned company in search of rescue. This time, however, the state broadcaster sees a way to use the law to enforce not so much its monopoly – which has long since been eaten away by competitors – but its right to claim a fee whether you watch SABC or not.

During the presentation to Parliament’s Portfolio Committee in October 2020, the SABC proposed using service provides such as Multichoice and content providers like Netflix to collect on its behalf. This will require a change in regulations to broaden the definition of a TV license to embrace newer platforms where people consume SABC content. It remains to be seen whether Multichoice and Netflix customers will comply with what may be seen as a cunning shake-down by the SABC.

The SABC provides 18 radio stations, five television channels as well as a digital media offering. Channel Africa is an additional radio station managed by the SABC on behalf of the government. Two other channels are delivered through DStv.

The three terrestrial television channels (SABC 1, 2 and 3) attract, on average, 28 million South Africans in a typical month. Seventeen of the nation’s top 20 television programmes are broadcast by the SABC’s television channels

It’s not hard to see why license fee delinquency is on the up. The annual fee is R265 but the fine for non-compliance may not exceed R500. Many people choose to take that rather low financial risk. Others prefer to get their content outside of the SABC and, certainly until recently, believe that they were paying for political propaganda.

Should the government decide in the middle of a Covid crisis, when income levels have collapsed, to take a battering ram to TV viewers in the hope of improving collection rates, there may well be a Constitutional Court challenge on the matter. After all, many South Africans long ago tuned out of SABC in favour of content more to their liking elsewhere.

What do you think? Should we support tougher enforcement of TV license fee collections? Or should the SABC ditch the license fees altogether and start finding more creative and less expensive ways to make up the revenue shortfall (such as through better, more targeted content)?